Cholera

Seething Wells Water - Surbiton’s Hidden Heritage

disease

Cholera - a greatly feared disease

Cholera was a greatly feared disease that could spread with speed and with devastating consequences. It arrived Britain in 1831 on a ship docking in Sunderland. It spread around the country causing an epidemic in that year. Epidemics also hit in 1848-49, 1854 and 1867.

In London it is thought 7000 people died of the disease in the 1831-32 outbreak which represented a 50% death rate of those who caught it. 15,000 people died in London in the 1848-49 outbreak. The disease usually affected those in a city’s poorer areas, although the rich did not escape.

The cause was simple. Sewage came into contact with drinking water and contaminated it. There was a lack of understanding of how it spread. The establishment, doctors, scientists, believed that cholera was spread through the air, not water. That is was miasmic. All people knew were the symptoms and the masses of bodies that needed to be buried.

An attack of cholera is sudden and painful. A victim would suffer severe h accompanied by painful gut cramps; extreme thirst and dehydration; severe pain in the limbs, stomach, and abdominal muscles; a change skin colour which left bodies bluish-grey.

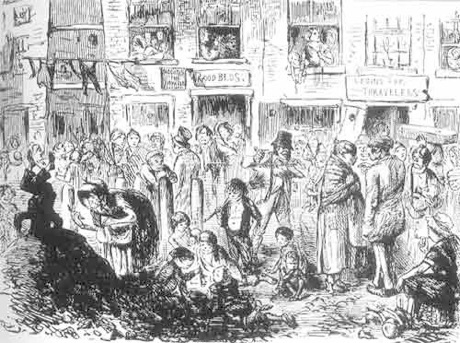

A much larger epidemic broke out in London in 1854. It spread in the most populated areas in London, such as Soho, Southwark, Lambeth and Broad Street. It was the worst that Britain had seen of Cholera. Life was a dreaded nightmare, people fled their homes and the streets and houses were filled with the stifling smells of the dead and the odours of the disease.

Dr John Snow was living near Broad Street at the time and carried out a crucial piece of research that helped understand how Cholera spread.

Cholera and Clean Water

By Bob Phillips

From ancient times, it was the medical orthodoxy that many infectious diseases emanated in a “miasma” from accumulated filth. This seemed to be corroborated by the fact that infectious diseases spread with frightening speed in poor, overcrowded, filthy areas of cities. When cholera arrived on the shores of Britain for the first time in the epidemic of 1831-2, the medical orthodoxy of miasma was assumed.

John Snow was not an orthodox society doctor. He was the son of a labourer in Northumberland, trained through an apprenticeship to a local apothecary (somewhat like a GP) from age 14. He encountered cholera first hand: when the first epidemic struck through the port of Sunderland, his master,William Hardcastle was fully stretched in Newcastle, and Snow, at 18, had to be the sole practitioner to the mining village if Killingworth, which was hard hit by the epidemic.

By the time John Snow was studying to be a doctor, in the 1830s, there were the beginnings of what would become new knowledge of the causation of disease. Van Leeuwenhoek, as early as the 17th century, had seen “animalcules” in water, under his new microscope. There were doctors, and Snow became one of them, who were reaching for a theory of disease caused by contagion. Snow came to London – he walked there! – in 1836, to complete a proper training in medicine, and he “put up his plate” in Soho in 1838. His first appearance on a wider stage in London was as what we would now call an anaesthesiologist – ether and chloroform were new tools then, and Snow went about exploiting them in a precise scientific manner. He did well – he attended on Queen Victoria for her confinement with Prince Leopold in 1843. This practice, with its mastery of the behaviour of gases, put Snow in a strong position to challenge some of the claims of the miasmatists, which he did even at the cost of appearing to be very eccentric when he defended the “noxious trades” against a charge of causing infectious disease.

As science developed in the eventual direction of understanding water-borne diseases, so was water engineering progressing. By the 1830, one water company, the Chelsea, had a brand new water sand-filtration system operating in the Thames at Pimlico, invented by a James Simpson, who will feature in our Seething Wells story. It is remarkable that Simpson’s new technology provided a way of trapping the disease-carrying bacteria in sludge decades before the bacteria had been identified.

Cholera struck Britain again in 1848-9. John Snow was personally involved in an outbreak at Albion Terrace, Wandsworth Road, where he discovered that the drains had been designed so as to all sewage-laden water to seep into the drinking water. This, and other evidence collected by John Grant, a Commissioner for Sewers, form Snow’s thoughts He published, at his own cost, a short book ‘On the Mode of Communication of Cholera’ in which he proposed fecalised water as bearing the agent for cholera. His theories did not get a wide audience.

By the end of the second cholera epidemic – 1849 – there were new many stream of activities. Government had passed the City Sewers Act caused a vast increase of the clearing of cess-pits (thought to be prime sources of miasma), and which had the side effect of making possible more systemic studies of what we would now call epidemiology, by making it easier for authorities to gather information from households – poor households, at least. The Lambeth water Company had decided – a very bold step – to develop a source of water outside the tidal basin of the Thames – they went to Seething Wells.

Then, in 1853, cholera invaded the shores of Britain again. John Snow saw in the actions of the Lambeth Water Company a golden scientific opportunity. The relatively clean water from Seething Wells was “on stream” from 1852 – Snow could compare households that were alike in every respect except that some took their water from Seething Wells, and the others from Battersea (The Lambeth & Vauxhall Water Company). Snow had to suspend his survey when the cholera came to his doorstep in Soho – hundreds of people were dying around Golden Square and Broad Street in September 1854. Snow worked with the local Vestry (the people responsible for the poor of the Parish), first convincing them to disable the pump at Broad Street that he was convinced was in the line of causation. And then working, with a local curate, Henry Whitehead, to show that, indeed, the water in that pump was infected (from a cess-pit into which the nappies of a cholera-infected baby had been rinsed.

John Snow published a second edition of his book, completing the “Grand Experiment” comparing the two sources of water, and publishing what they had discovered in Broad Street. For him, it was convincing proof that cholera was water borne. But the world did not abandon its orthodox prejudice for miasma as easily as that. There was a much bigger study, exactly on the lines of Snow’s groundbreaking study, conducted officially, which proved more convincing evidence. (The author of this study, John Simon, failed to acknowledge Snow’s prior work, which caused a great furor.) But it was not until a further epidemic – 1866 – that people really came round to the view that Snow had the truth. Sadly, Snow had died by then, in 1858, at the age of 45.

By then, all of the water companies serving London had been compelled to follow the example of Lambeth, and source their water from outside the tidal Thames. The Chelsea Water Company was the last to move, in 1855, and they followed Lambeth exactly, to the Seething Wells site.

As the civil engineers moved forward with the times, so did medicine. Pasteur established in 1864 that specific diseases are caused by specific microbes; this changed the scientific context hugely by the time the final cholera epidemic had worked itself out in 1867. In 1883 Koch isolated the specific bacillus that causes cholera, and in 1895 a vaccine was developed and tested in India, by Haffkine.

Dr John Snow

epidemiology

Dr John Snow - one of the founders of epidemiology

Dr John Snow was a British physician who is considered one of the founders of epidemiology for his work identifying the source of a cholera outbreak in 1854.

John Snow was born into a labourer’s family on 15 March 1813 in York and at 14 was apprenticed to a surgeon. In 1836, he moved to London to start his formal medical education. He became a member of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1838, graduated from the University of London in 1844 and was admitted to the Royal College of Physicians in 1850.

At the time, it was assumed that cholera was airborne. However, Snow did not accept this ‘miasma’ (bad air) theory, arguing that in fact entered the body through the mouth. He published his ideas in an essay ‘On the Mode of Communication of Cholera’ in 1849. A few years later, Snow was able to prove his theory in dramatic circumstances. In August 1854, a cholera outbreak occurred in Soho. After careful investigation, including plotting cases of cholera on a map of the area, Snow was able to identify a water pump in Broad (now Broadwick) Street as the source of the disease. He had the handle of the pump removed, and cases of cholera immediately began to diminish. However, Snow’s ‘germ’ theory of disease was not widely accepted until the 1860s.

Snow was also a pioneer in the field of anaesthetics. By testing the effects of controlled doses of ether and chloroform on animals and on humans, he made those drugs safer and more effective. In April 1853, he was responsible for giving chloroform to Queen Victoria at the birth of her son Leopold, and performed the same task in April 1857 when her daughter Beatrice was born.

Snow died of a stroke on 16 June 1858.

The Broad Street Pump

How did it happen?

Water Pump

In the 1854 epidemic there was a ferocious outbreak in Soho, on Dr. Snow’s doorstep. From his earlier researches, Snow was sure that the cause would be in the water supply, and he rapidly observed that there was a pattern of deaths among people for whom a pump in Broad Street was the most convenient supply. He acted with determination on this conviction, and persuaded the Parish vestry-men to disable the pump.

Snow continued his researches, aided by the local curate, Henry Whitehead, and all the data supported him, including such evidence as the death of the widow Susannah Eley, far away in Hampstead, discovered to have had water from Broad Street sent to her because she had become accustomed to its taste when she lived in Soho!

The negative data also supported Snow: the brewery-men in Soho who escaped the cholera had been drinking beer, not water. The family of four living in Broad Street who survived without any symptoms. The parents insisted they always drew water from the Broad Street pump. But Whitehead discovered that their little girl, whose job was to fetch water, had a bad cold at the time, and the family had been using water from the cistern in the house.

The outbreak in Soho died away, after claiming 720 victims in two weeks. Snow’s action may have shortened the outbreak – probably only by a little, but his researches in Soho and elsewhere had a gigantic impact on the control of cholera.

© 2022 Proof from Seething Wells